Mornings with Marcel

On reading Proust's In Search of Lost Time

As 2022 was ending, a growing sense of ‘now what?’ crept in. I’ve had some sort of project on the go for as long as I can remember — a degree, a book, a move — so arriving at a place of completion was unfamiliar and uncomfortable. In the miniature house of my brain, the project room was noticeably vacant, an empty sunlit space, all naked windows and bare wood floors. Move-in ready for the next endeavour. But I was leery of that too, aware that there might be something about projectlessness to savour. The answer to this dilemma, as to many of my life’s questions, came in the form of reading. I decided 2023 would be the year I tackled Marcel Proust’s six volume opus In Search of Lost Time.

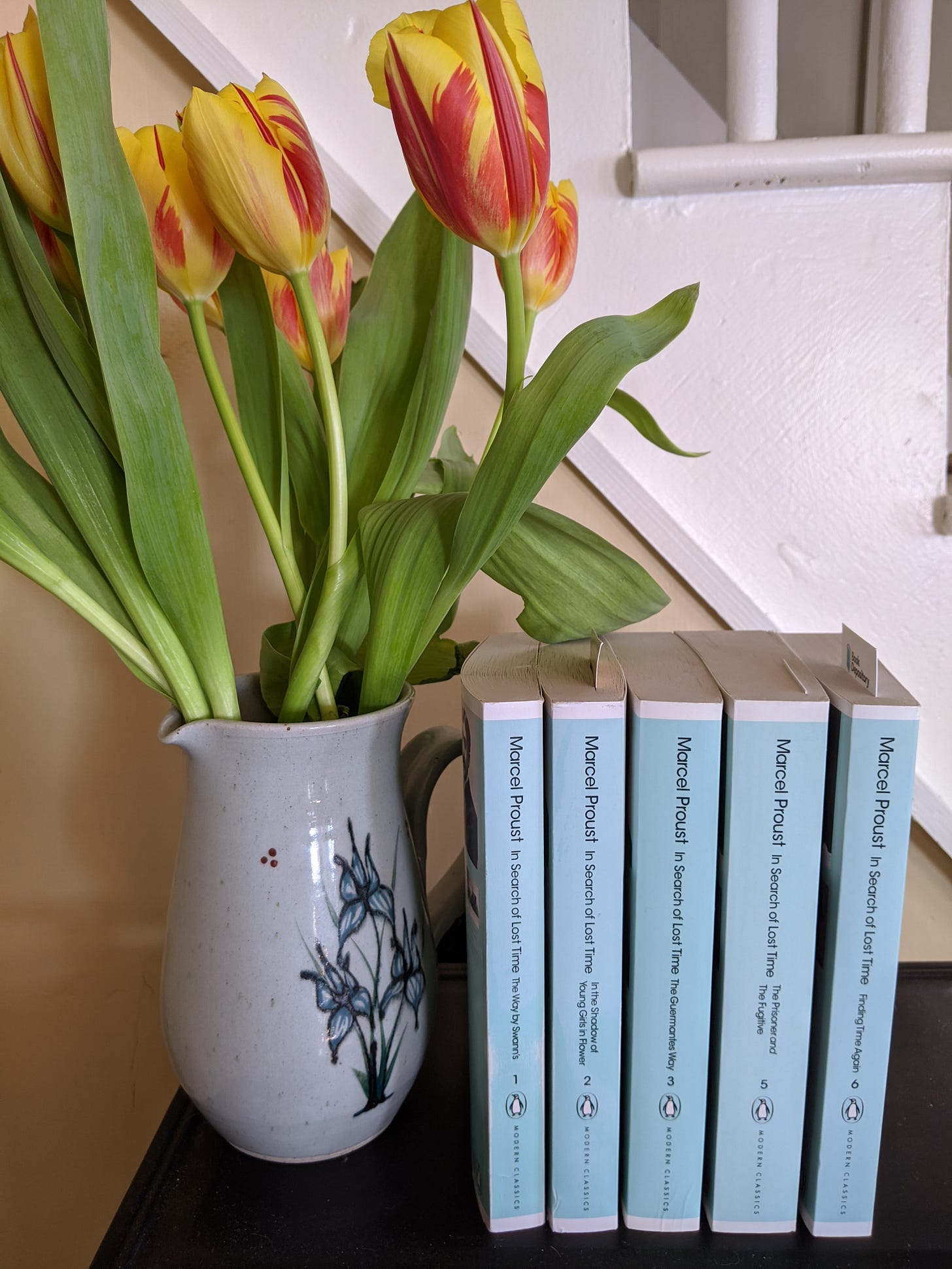

By mid-January a pretty stack of Modern Classic Penguins with mint-green spines were delivered (curiously minus Volume 4), and thus began my mornings with Marcel. Each day begins with coffee and Proust. Some days I read twenty pages, other days I only manage four. The type is tiny and dense. One sentence, full of asides, intricacies, and analogies, can last a page. It requires slow reading.

I am mid-way through volume two, and I am loving it, even the boring parts, even the parts that make my eyes roll. (One would not describe this work as feminist.) I have no intention to try and recap it. Things do happen (lots of obsessive love affairs), but one doesn’t read Proust for the plot. Instead, as the title suggests, it is about time and memory. It’s a very phenomenological book, capturing the texture of experiences and the richness of one’s interiority. Things are happening in the world, but what matters most is what’s happening within an individual’s mind, heart, and soul. To paraphrase the narrator, to see things only from the outside is to see nothing (394).

Proust’s epic does not feel like a young person’s book. To appreciate its brilliance, it helps to have experienced a significant passage of time, that sense of loss that comes with aging, that gap between what was and what is now. The book is steeped with nostalgia. The last volume ends with the reminder that “the memory of a certain image is only regret for a certain moment; and houses, roads, avenues are as fleeting, alas, as the years” (430). Having moved back to my hometown after 20+ years, this sentence struck me. It has taken a while for my ‘map’ of Saint John to reflect how the city is now, and not as I remember it from 1998. And just as biting into a madeleine cookie launched Proust into a meditation on his past, so too can a stoplight make me remember something of what it was to be 10, 15, or 25. There are moments when I experience multiple versions of Saint John (how I remember it, how I thought it would be, how I am living it now) and myself (young me, who I thought I’d be, current me) simultaneously. Amazingly, Proust is able to write about this internal emotional landscape in a way that is comprehensible and illuminating.

And sometimes his writing is exquisite. This description of lilacs is perfect:

Lilac-time was nearly over; a few, still, poured forth in tall mauve chandeliers the delicate bubbles of their flowers, but in many places among the leaves where only a week before they had been breaking in waves of fragrant foam, a hollow scum now withered, shrunken and dark, dry and without perfume (137).

I’m discovering In Search of Lost Time offers a particular kind of reading experience, which is why multiple articles and memoirs have been written about reading it. Maybe I will check them out once I am done, to compare notes. For now. I am enjoying the project of reading Proust, so much so it doesn’t even feel like a project.

And few postscripts…

The ghost of Lord Beaverbrook be damned, our book is now out.

The province of NB has officially launched its 2023 spring river watch, reminding me that my River Watch is almost a year old.

Here’s a good poem about reading Proust.

“The Summer You Read Proust” by Philip Terman

Remember the summer you read Proust?

In the hammock tied to the apple trees

your daughters climbed, their shadows

merging with the shadows of the leaves

spilling onto those long arduous sentences,

all afternoon and into the evening-robins,

jays, the distant dog, the occasional swaying,

the way the hours rocked back and forth,

that gigantic book holding you in its woven nest-

you couldn’t get enough pages, you wished

that with every turning a thousand were added,

the words falling you into sleep, the sleep

waking you into words, the summer you read

Proust, which lasted the rest of your life.

from Our Portion. © Autumn House Press, 2015. And found here.